2019

C-Type print

98 x 74 cm

Edition of 5

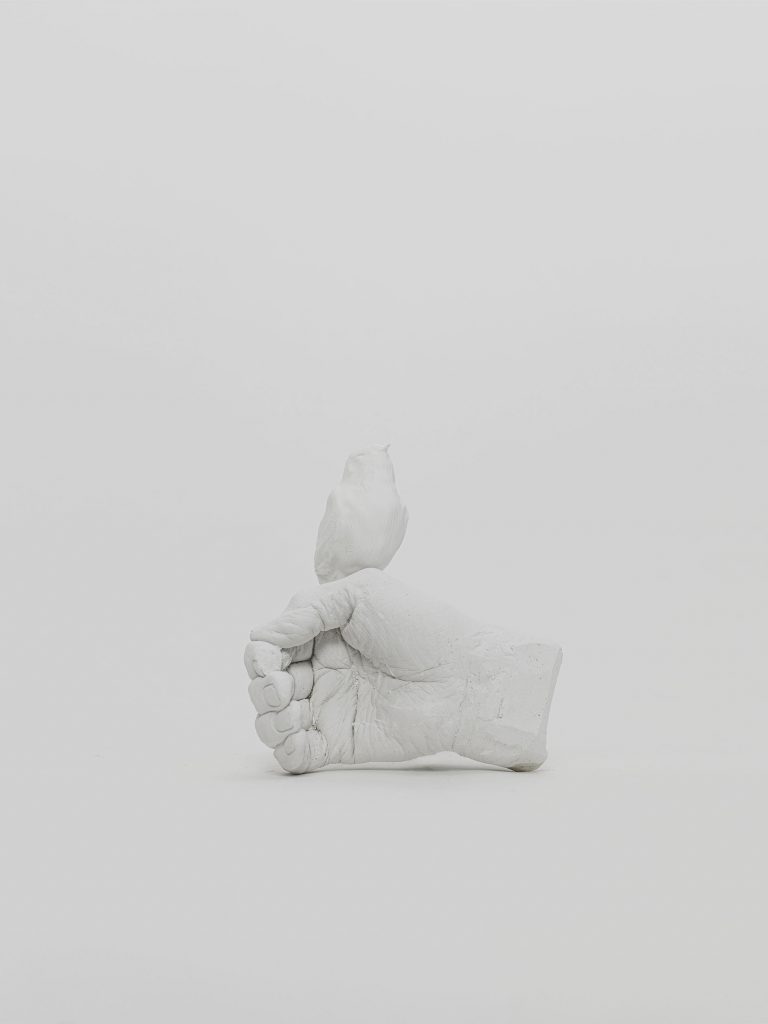

Dusky seaside sparrow

In 1979 and 1980, a captive breeding program was established. However, only seven dusky seaside sparrows were located and they were all male. Because there were no females left to help reproduce the species, the captive breeding program brought in females from a closely related subspecies of sparrow.

Cross-breeding attempts, such as this, are designed to preserve some of the genetic diversity represented by a species. The female offspring of the cross-bred pair could then breed with the other male dusky seaside sparrows.

Through this kind of breeding, an individual with a very high percentage of dusky seaside sparrow genes could live to carry on much of the genetic diversity that would otherwise be lost. Unfortunately, the cross-breeding attempts were unsuccessful. The last dusky seaside sparrow died in captivity in 1987.

2019

C-Type print

98 x 74 cm

Edition of 5

Least Vermilion Flycatcher

During a survey in 1929 ornithologist Albert Kenrick Fisher found this bird rather abundant all along the arid western coast to the settlement of Progreso in the highlands. During the next sixty years invasive plants replaced a large part of the endemic vegetation which led to the decline of the insects which were dependent on the endemic plants. When David and Lee Steadman visited San Cristobal Island in the 1980s they described the San Cristóbal vermilion flycatcher as extremely rare. The last reliable sighting was in 1987. Finally, a six-month expedition in 1998, failed to find any birds. After a long-term-study since 2012, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust described it as “first bird extinction in Galapagos” in June 2016.

2019

C-Type print

98 x 74 cm

Edition of 5

2019

C-Type print

98 x 74 cm

Edition of 5

2019

C-Type print

98 x 74 cm

Edition of 5

Black-faced honey creeper

By 1997, only three individuals were known to exist. These had home ranges within the Hanawi Natural Area Reserve and the near Haleakala National Park.

On September 9, 2004, one of the remaining birds, a male, was captured and taken to the Maui Bird Conservation Center in Olinda, in an attempt to breed the bird in captivity. However, biologists could not find a female for the male before it died on November 26, 2004.

A 2018 study recommended declaring the species extinct, citing bird population decline patterns and the lack of any confirmed sightings since 2004.

Lost to sight (2019) is a series of photographs showing small, white sculptures of birds sitting on hands. Some of which are closed like a fist, while others are open. The birds are examples of extinct species, and we see among others the Black-faced honeycreeper and the Least Vermilion flycatcher. Even though the photographs are all monochromatic and minimalistic, and the shadows from the sculptures are the main sign of space in the photographs, the picture space is compound. In this space numerous versions of materiality, technology, stories, and sculptural processes are present at the same time: The materiality of the picture space is highlighted by the visible processes of the traditional plaster casting of the hands, the digital 3D printing of the birds based on sketches and images, and the sculptural arrangement of hand and bird.